I have taught regenerative grazing to hundreds of farmers and supported dozens of regenerative transitions, helping craft detailed grazing plans that optimise grass growth.

I can assure you that regenerative grazing works.

Regenerative grazing can help farmers create resilient, biodiverse swards that consistently produce high-quality forage.

Rothamstead’s recent study, which demonstrated that ‘cell’ grazing doubled the carrying capacity of the site being studied, supports this claim.

It’s great being able to grow grass consistently and, as soil health improves, increase the nutrient density of your forage. However, there’s a commonly overlooked factor in regenerative grazing that can turn a good regenerative grazing system into a great regenerative grazing system.

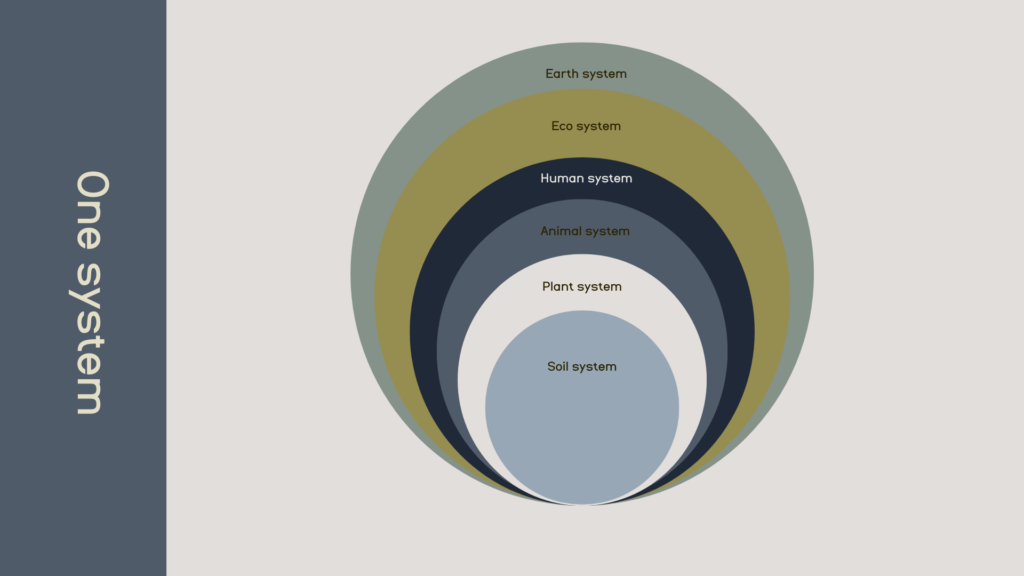

I take a ‘whole system’ approach to management. As part of my ROOTED framework, I use this holon model to understand and manage the design and transition to a regenerative system.

If we only focus on the ‘plant’ part of the holon, managing our grazing for the most productive grass plant, we will design our grazing around and pander to the grass plant. We will conclude that non-selective grazing with multiple moves a day grows the most grass, and our recovery rates are tightly tailored to ensure that the grasses don’t become too mature and lose quality or—god forbid—senesce and be allowed to go to seed!

We can back this up with science that shows that the best carbon sequestration rates happen from non-selective grazing with four moves a day managing for green growing plants. We might focus on the productivity of the individual plants and can even justify continued fertiliser use based on this logic – more green grass = more carbon sequestration.

All that’s true if viewed from this narrow lens, but this is a partial piece of a much more complex ‘whole’ picture of productivity.

If we widen the lens to include the outer ‘holons’ of the livestock and ecosystem, then we might come to a different conclusion – I have!

By focusing on one productive grass plant species and managing for its rapid reproduction cycle, you inadvertently prevent the development of a functional whole pasture system.

A functional pasture system includes a mixture of legumes, grasses, and wildflowers, each with its own superpowers. Each species brings something different to the party and helps to create an ‘overyielding’ effect, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

With such a plant community, longer recoveries are required to maintain the diversity – and yes, some of the sward will become mature – but overall, there’s a fabulous mixture of plant species at all growth stages, each benefiting our livestock in different ways.

In my ten years of working on regenerative grazing systems, I have never found a beef or sheep farmer who wanted to move their livestock four times a day. This level of staffing and infrastructure is usually unachievable and unprofitable for most grass-based UK farms. We need flexible regenerative grazing systems that work for farming families.

We live in an environment where our farms are small, and summers are short. Do we want to graze or cut grass down to the soil, leaving it bare and exposed and unable to capture the limited sunshine we receive in a growing season? I prefer to create a functional whole plant system where the taller canopy creates a mini rainforest microclimate of growy conditions, reducing evaporation and encouraging the rapid mineral cycle required to build a healthy soil food web that can unlock nutrients normally unavailable to our plants. That sort of system is resilient to drought and flood and highly productive.

But that’s not even the biggest missed opportunity to optimise a regenerative grazing system.

If you look at the ‘livestock’ section of the regenerative holon, you realise this is an often overlooked vital piece of the ‘whole’ regenerative production puzzle.

Suppose you have a cow bred to convert highly digestible, high protein and energy forages into meat or milk, and you graze them on this more mature sward. In that case, you can expect poor results – especially if the sward is a ryegrass sward that’s all headed at the same time!

However, if you graze livestock that have been genetically selected for pasture production and adapted to more mature swards, they will absolutely thrive on these more mature grazing systems, achieving daily live weights comparable with those of housed systems feeding concentrates.

If the livestock are part of a whole herd system where the mother can teach the daughter/son, they will benefit from the ready-adapted rumen microbiome and develop site-specific nutritional wisdom.

The animals will know what plants contain the exact nutrients they need, what order to eat them, and in what ratio to optimise their own productivity.

In design, ‘smart’ technology refers to the integration and interconnectivity of intelligent and automatic devices that can enhance different aspects of function.

To get ‘smart’ cows we need to design ‘smart’ farming systems with a ‘whole system’ livestock selection process.

In livestock breeding, whenever we select for certain traits, we inevitably lose others – you can’t have everything, and some traits are antagonistic.

If we design a breeding and selection process focusing on ‘production’ metrics such as weaning weights, we might lose the broader ‘whole system’ traits that could lead to a more profitable farm in your unique context.

For example, by selecting a weaning weight EBV (WWT), you might be aiming for an increase in the growth of a calf in proportion to its mother’s weight. But why has it grown more? Is it growing more because its growth hormones are dominant over reproductive hormones, so it has grown more bone? Or it might have been super efficient with calories and put more energy into growing muscle rather than fat, which may work for the steers heading to the store sale, but when the retained heifers can’t build body fat in Autumn, lose condition through winter and don’t get into calf every year we might be sorry!

We could be selecting for feed efficiency (something being pushed to reduce methane emissions), which may inadvertently lead to animals with less diversity and flexibility in their gut microbiome that perform poorly on diverse or mature forages.

The most profitable farming system for you might be a regenerative grazing system based on livestock that reach sexual maturity early, live a long life and get in calf/lamb every year whilst holding their condition and rearing a stonking calf/lamb on forage only then naturally weaning and giving birth with no fuss.

When focused on single metrics, it is easy to forget the skills of traditional farming wisdom and good stockmanship skills. We have lost something essential for building a resilient and regenerative farming system.

In our Grazing School Genetics Day (and Roots to Regeneration/Wilderculture Approach programmes), we cover how to design your regenerative breeding strategy.

Learn from Rob Havard and James Rebanks, two highly experienced regenerative farmers who have been re-learning and blending this age-old wisdom with modern science and applying it in a range of contexts.